The noted blogger Fjordman is filing this report via Gates of Vienna.

For a complete Fjordman blogography, see The Fjordman Files. There is also a multi-index listing here.

Dymphna of Gates of Vienna recommended to me a book called “Eccentric Culture: A Theory of Western Civilization,” by Rémi Brague. The Romans admired the earlier culture of the Greeks. Christians had a love/hate relationship with Judaism, but they did recognize that the Jews had an older religious tradition than they did themselves, and that they were greatly indebted to it. Christian Europeans thus inherited a twin “cultural secondarity” in relations to their Greek and Hebrew parent cultures. Brague sees this phenomenon of secondarity as the very essence of the Latin West, and dubs it “Romanity.”

According to him, “All that the most severe judges are willing to concede to Romanity is that Rome spread the riches of Hellenism and transmitted them down to us. But this is precisely the important fact — everything changes if one stops examining the content of the Roman experience only, and instead turns to the transmission itself. This one little thing that is conceded to be properly Roman is perhaps the whole of Rome… The Romans have done little more than transmit, but that is far from nothing. They have brought nothing new in relation to those two creator peoples, the Greeks and the Hebrews. But they were the bearers of that innovation. They brought innovation itself. What was ancient for them, they brought as something new.”

According to him, “All that the most severe judges are willing to concede to Romanity is that Rome spread the riches of Hellenism and transmitted them down to us. But this is precisely the important fact — everything changes if one stops examining the content of the Roman experience only, and instead turns to the transmission itself. This one little thing that is conceded to be properly Roman is perhaps the whole of Rome… The Romans have done little more than transmit, but that is far from nothing. They have brought nothing new in relation to those two creator peoples, the Greeks and the Hebrews. But they were the bearers of that innovation. They brought innovation itself. What was ancient for them, they brought as something new.” As Edward T. Oakes says in First Things magazine:

One of the standard prejudices of philosophers plying their trade in the West is the notion that Latin is more impoverished than Greek for expressing the nuances of metaphysical speculation (Heidegger felt the same about the virtues of German over French or English). Whether true or not, Latin certainly served as a linguistic bonding agent in the European West in a way not paralleled by any other language in the world. As Brague argues, Latin ‘suffers’ from a triple secondarity: 1) it was no one’s mother tongue after the collapse of Rome; 2) it was never a deliberately coined Christian language, but the language of the Roman Empire, a political rather than a religious entity and one that antedated Christianity by centuries and was mostly hostile to it; 3) it was the language of the officially recognized Bible in the West (the Vulgate), but the Scriptures themselves were originally written in Hebrew and Greek. The Vulgate, therefore, perfectly expresses the essentially Roman (that is, secondary) feature of Christianity, whose originating ‘Greeks’ are the Jews.

One of the great ironies of history is that the Greek legacy rediscovered by Westerners via the Byzantines had an arguably greater impact in the West than it did in the Byzantine Empire itself. Although the Byzantines called themselves “Romans,” which was certainly true in the sense of institutional continuity, we should remember that for the original, Latin-speaking Romans, Greece represented a great, but still essentially foreign culture. The diminished Byzantine Empire after the Arab conquests encompassed a predominantly Greek-speaking region. The people who lived there didn’t view the ancient Greeks as “the Other,” but as their ancestors. To them, Greek philosophy was “theirs,” hence they didn’t reflect as much over it as some outsiders did. To Westerners, it was new and exciting and at the same time a part of a forgotten past, a legacy of an older civilization, hence they greeted it with greater enthusiasm.

If we state that what created the Scientific Revolution in the West was the combination of the Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian impulses, we have to explain why the same thing didn’t happen in the Byzantine Empire. There are several possible explanations:

| 1. | The Byzantine Empire spent too many resources on fighting Jihad, all the while being a bulwark against Islamic expansion deeper into Europe. There is some truth in this, but we should remember that Muslims did manage to penetrate deep into Western Europe, too, and controlled the Iberian Peninsula for centuries. The West was not free from Jihad, either. | |

| 2. | Theological differences. Although both the Byzantines and Westerners were Christians, there were subtle, yet potentially important differences in theology, for instance in the emphasis on work as a way of worshiping God, which was stronger in the Catholic West (and arguably even more in the Protestant West later) than in the Orthodox East. | |

| 3. | Structural differences. The Byzantine Empire had a more centralized, bureaucratic power structure than did the West, which was divided into many competing states, had more internal power centers and a split between church and state created by the Papal Revolution. Structurally speaking, the Byzantine Empire probably resembled China more than the West, although it was certainly smaller than China. | |

| 4. | The Byzantines never understood the Crusaders’ passion for the Holy Land because for them Jerusalem, although now under Islamic control, was still “theirs.” The original Byzantine Empire geographically encompassed both the Hebrew and the Greco-Roman roots of European culture. The Byzantines saw themselves as the center of civilization in a way Westerners could not and did not do. In this, they also resembled the Chinese. |

As Brague points out, Christians do recognize that the Hebrew Bible is valid and authentic. Muslims, on the other hand, believe that Christians and Jews have falsified their texts, which accordingly have no specific value in themselves:

One should be careful, therefore, not to make an implicit analogy between what one calls, with an expression that besides is quite superficial, the ‘three monotheisms.’ Islam is not to Christianity (not even to Christianity and to Judaism) what Christianity is to Judaism. Admittedly, in both cases, the mother religion rejects the legitimacy of the daughter religion. And in both cases the daughter religion turned on its mother religion. But on the level of principles, the attitude toward the mother religion is not the same. While Islam rejects the authenticity of the documents on which Judaism and Christianity are founded, Christianity, in the worst case, recognizes at least that the Jews are the faithful guardians of a text that it considers as sacred as the text which is properly its own. In this way, the relationship of secondarity toward a preceding religion is found between Christianity and Judaism and between these two alone.- - - - - - - - -

Europeans have always recognized that Europe is a younger culture compared to Egypt and the Near East. The cradle of civilization was always “somewhere else.” As Ibn Warraq demonstrates in his book Defending the West: A Critique of Edward Said's Orientalism, the ancient Greeks admired the civilizations of Egypt and the Near East, but the crucial difference is that although they readily admitted to borrowing from these older civilizations, they didn’t incorporate their religions and texts into their own culture unchanged. They assimilated outside influences, which didn’t give them the same permanent cultural secondarity as the Romans developed towards them later.

Europeans have always recognized that Europe is a younger culture compared to Egypt and the Near East. The cradle of civilization was always “somewhere else.” As Ibn Warraq demonstrates in his book Defending the West: A Critique of Edward Said's Orientalism, the ancient Greeks admired the civilizations of Egypt and the Near East, but the crucial difference is that although they readily admitted to borrowing from these older civilizations, they didn’t incorporate their religions and texts into their own culture unchanged. They assimilated outside influences, which didn’t give them the same permanent cultural secondarity as the Romans developed towards them later. As Brague says, “on the collective level, every culture is the heir of the one or several that preceded it. In this sense, every culture is a land of immigration. But there is more: cultural secondarity seems to me to have, in the case of Europe and of it alone, a supplementary dimension. Europe has indeed this special feature of having, one might say, immigrated to itself. I mean by this that the secondary character of the culture is not only present there as a fact, but is explicitly recognized and deliberately desired.”

In the history of Europe, “one witnesses a constant effort to go back up toward the classical sources. One can thus describe the intellectual history of Europe as an almost uninterrupted train of renaissances.” For example, “One can then begin with the ‘Carolingian Renaissance,’ proceed to the ‘Renaissance of the Twelfth Century,’ and continue, of course, with the series of Italian Renaissances. But one could not stop there, because one finds the German cycle of Hellenism in the same line. One can make it begin with Winckelmann — unless one insists on going back to Beatus Rhenanus. Weimar classicism then followed and resulted in the dream of becoming Greeks once again.”

As Rémi Brague explains, this situation of secondarity in relation to the past aimed at by the “renaissances” in Western Europe was alien to Byzantium: “Admittedly, one does not have any trouble locating, in the cultural history of the Byzantine world, an uninterrupted ‘humanist’ tradition. One sees there a series of ‘renaissances’ follow one after the other, which constitute the counterpart, and often the model or a more or less direct motor, for analogous events occurring in Europe: the reestablishment of philological and literary studies in the ninth century with Photius or in the fourteenth with John Italus and Michael Psellus, and even in a dream of Neo-Paganism in George Gemistus Plethon in the fifteenth century. But the great difference is that, for the Byzantine Greeks, Hellenism was considered as their proper past. Theodorus Metochites [in the fourteenth century] could still affirm: ‘We are the compatriots of the ancient Hellenes by race and by language.’ For the Byzantines, it was only a matter of appropriating better and better what had always been their property.”

As Rémi Brague explains, this situation of secondarity in relation to the past aimed at by the “renaissances” in Western Europe was alien to Byzantium: “Admittedly, one does not have any trouble locating, in the cultural history of the Byzantine world, an uninterrupted ‘humanist’ tradition. One sees there a series of ‘renaissances’ follow one after the other, which constitute the counterpart, and often the model or a more or less direct motor, for analogous events occurring in Europe: the reestablishment of philological and literary studies in the ninth century with Photius or in the fourteenth with John Italus and Michael Psellus, and even in a dream of Neo-Paganism in George Gemistus Plethon in the fifteenth century. But the great difference is that, for the Byzantine Greeks, Hellenism was considered as their proper past. Theodorus Metochites [in the fourteenth century] could still affirm: ‘We are the compatriots of the ancient Hellenes by race and by language.’ For the Byzantines, it was only a matter of appropriating better and better what had always been their property.” True, as Timothy Gregory writes in A History of Byzantium, by the twelfth century there was a new individuality in Byzantine arts: “The mosaics and frescoes of the period abandon the abstractness of earlier art and the figures are depicted more in a three-dimensional view and with a real sense of movement.” This is unlike the stylized paintings that became the direct ancestors of the religious icons made by Russians, Bulgarians, Serbs and other Orthodox Christians who consider themselves the heirs of Byzantium. These icons can be very beautiful, but they are distinctly different from later Western art.

It would obviously be untrue to claim that Byzantine art or culture was unaffected by the Classical heritage. However, it is significant that the Italian Renaissance and the revolutionary realism it introduced in describing nature, which was also arguably mirrored in science, marked a permanent change in Western art. Nothing equivalent ever happened in Byzantium. This also had practical consequences tied to science. In Western Europe, technical drawings, scale drawings and development of models were later aided by advances in mathematics and the development of geometrical perspective in painting during the Renaissance.

The 20th-century Austrian historian of Byzantine art Otto Demus explains that in the “renaissances” in the West and at Byzantium, the intention and the direction were similar. However, “the Occidental renaissances were of shorter duration, of less intensity, and separated from each other by intervals during which the tendency went entirely in the opposite direction. The Byzantine renaissances, conversely, followed nearly without a resolution of continuity, they were only nodal points on which forces were concentrated and efforts were almost always there. This is why one is right to speak of a ‘permanent renaissance’ in Byzantium. But as a consequence these concentrations lacked tendencies that aimed at just what characterizes an authentic renaissance: Antiquity was for the Byzantines something so near that it could not establish the feeling of estrangement which would drive creation [schöpferisches Fremdheitserlebnis] and so nothing could truly be ‘reborn.’”

In contrast, according to Brague, Western Europeans had “a consciousness of being latecomers, and of having to go back to a source that ‘we’ are not and which has never been ‘us.’ This consciousness is vivid from the beginning of the European project. It is even, perhaps, the motor of its history.”

For instance, Charlemagne, whom one nicknamed “the father of Europe” (Pater Europae), “dreamed of competing with Byzantium, in comparison with which, despite its then-weakened state, he could not help but feel inferior. Byzantium had all the signs of legitimacy: material riches (‘the gold of Byzantium’), a dynasty, the Roman name (the second Rome), manuscripts and scholars to read them, and numerous saints’ relics that were signs of the continuity of the Church from its apostolic foundation. In his biography of Charlemagne, Einhard recounts that the emperor had bequeathed three tables of silver and one of gold in his will. On the first were represented, respectively, the maps of Constantinople and of Rome, and a map of the entire world. One will note that two maps are conspicuous by their absence: among maps of cities, that of Aachen, the capital of the Carolingian Empire. This city must at that time cut a poor figure alongside the two reference points which Europe never ceased ogling, the two Romes, the ancient and the contemporary. But also missing was a map of Europe, the newly founded empire of the Occident. Its founder could not gaze at himself complacently in the image of his creation.”

For instance, Charlemagne, whom one nicknamed “the father of Europe” (Pater Europae), “dreamed of competing with Byzantium, in comparison with which, despite its then-weakened state, he could not help but feel inferior. Byzantium had all the signs of legitimacy: material riches (‘the gold of Byzantium’), a dynasty, the Roman name (the second Rome), manuscripts and scholars to read them, and numerous saints’ relics that were signs of the continuity of the Church from its apostolic foundation. In his biography of Charlemagne, Einhard recounts that the emperor had bequeathed three tables of silver and one of gold in his will. On the first were represented, respectively, the maps of Constantinople and of Rome, and a map of the entire world. One will note that two maps are conspicuous by their absence: among maps of cities, that of Aachen, the capital of the Carolingian Empire. This city must at that time cut a poor figure alongside the two reference points which Europe never ceased ogling, the two Romes, the ancient and the contemporary. But also missing was a map of Europe, the newly founded empire of the Occident. Its founder could not gaze at himself complacently in the image of his creation.” Brague states that “Charlemagne could thus see the place his own Occidental empire occupied, far from the centers, far from Jerusalem, far from everything — eccentric. He tried to be linked to Byzantium first by competing with it, and even in aping it — in architecture, for example: the basilica of Aachen imitates that of Ravenna, the single accessible example of Byzantine architecture.” He also dared to have himself crowned emperor of the Occident. All of this rested on an admission: “Legitimacy was elsewhere, it came from elsewhere.”

While in the Orient the Byzantine Emperor, who besides received liturgical prerogatives at his coronation, made and unmade the Patriarchs, the Occident followed another course. This may have been for reasons that one can consider as purely historical contingencies, and even as completely bad (the Pope was also a head of state, had privileges to defend etc.). The fact remains that, in the Latin Occident, a non-conflictual union of the temporal and the spiritual, which was not less dreamed of here than elsewhere (‘union of the throne and of the altar,’ or the theocratic dreams of certain Popes, etc.), has never been a historical reality. In Byzantium the situation was less clear.” There “the idea of a ‘symphony’ (a harmonious agreement) of the temporal power of the Emperor and of the spiritual power of the Patriarch tended to confound the two much more than in the Occidental theory of the ‘two swords.’

This had major long-term consequences for the growth of political liberty in the West: “In actuality, the Russian Orthodox clergy was brutally forced into submission to the Tsar starting with Peter the Great. In contrast, the Pope has always constituted, in the Occident, an obstacle to the ambitions of emperors and kings. This conflict is perhaps what has allowed Europe to maintain that singularity which has made it a unique historical phenomenon. Its importance was clearly seen by Lord Acton, who wrote: ‘To that conflict of four hundred years we owe the rise of civil liberty. If the Church had continued to buttress the thrones of the king whom it anointed, or if the struggle had terminated speedily in an undivided victory, all Europe would have sunk down under a Byzantine or Muscovite despotism’ It was this conflict that prevented Europe from changing into one of those empires that reflected an ideology in their manner and their image — whether they produced it or pretended to incarnate it.”

This had major long-term consequences for the growth of political liberty in the West: “In actuality, the Russian Orthodox clergy was brutally forced into submission to the Tsar starting with Peter the Great. In contrast, the Pope has always constituted, in the Occident, an obstacle to the ambitions of emperors and kings. This conflict is perhaps what has allowed Europe to maintain that singularity which has made it a unique historical phenomenon. Its importance was clearly seen by Lord Acton, who wrote: ‘To that conflict of four hundred years we owe the rise of civil liberty. If the Church had continued to buttress the thrones of the king whom it anointed, or if the struggle had terminated speedily in an undivided victory, all Europe would have sunk down under a Byzantine or Muscovite despotism’ It was this conflict that prevented Europe from changing into one of those empires that reflected an ideology in their manner and their image — whether they produced it or pretended to incarnate it.” Rémi Brague’s conclusion is that “when all is said and done, the cultural poverty of Europe has been her good fortune. It obliged it to work and to borrow. On the contrary, the richness of Byzantium paralyzed it, got in its way, because it had no need to look elsewhere. This has been noticed in regard to the history of art. One noticed it equally in regard to philosophy.”

”The consciousness that Europe had of having its sources outside of itself had the consequence of displacing its cultural identity, such that it has no other identity than an eccentric identity. It is now fashionable to hurl at European culture the adjective ‘eurocentric.’ To be sure, every culture, like every living being, can’t help looking at the other ones from its own vantage point, and Europe is no exception. Yet, no culture was ever so little centered on itself and so interested in the other ones as Europe. China saw itself as the ‘Middle Kingdom.’ Europe never did. ‘Eurocentrism’ is a misnomer. Worse: it is the contrary of the truth.”

Kenneth Pomeranz in The Great Divergence — China, Europe and the Making of the Modern World claims that “as late as the mid-eighteenth century, Western Europe was not uniquely productive or economically efficient.” Pomeranz belongs to the school of historians who believe that it wasn’t until the full effects of the Industrial Revolution set in during the nineteenth century that Western technological and economic superiority became undeniable. According to this view, as late as the year 1800, there were regions in Asia that matched Western Europe in terms of wealth and health. Some regions in India and to a lesser extent Southeast Asia did, but especially in China and Japan:

”….there is good reason to think that ‘luxury’ demand was at least as dispersed among various classes of Chinese and Japanese as it was among Europeans. And as we have already seen at some length, when it came to matters of ‘free labor’ and markets in the overall economy, Europe did not stand out from China and Japan; indeed, it may have lagged behind at least China. At the very least, all three of these societies resembled each other in these matters far more than any of them resembled India, the Ottoman Empire, or southeast Asia. Thus, at least so far, we would seem to have similar conditions in these three societies for the emergence of the new kinds of firms that we generally think of as ‘capitalist.’”

I will leave out the details of his argument for now. Let’s assume that China and Japan had a roughly equal capacity to challenge the West in the nineteenth century. If so, how come Japan did so quickly, but China was slower and less efficient in meeting the new challenge?

As Jared Diamond says in Guns, Germs and Steel, “Firearms reached Japan in A.D. 1543, when two Portuguese adventurers armed with harquebuses (primitive guns) arrived on a Chinese cargo ship. The Japanese were so impressed by the new weapon that they commenced indigenous gun production, greatly improved gun technology, and by A.D. 1600 owned more and better guns than any other country in the world. But there were also other factors working against the acceptance of firearms in Japan. The country had a numerous warrior class, the samurai, for whom swords rated as class symbols and works of art (and as means for subjugating the lower classes). Japanese warfare had previously involved single combats between samurai swordsmen, who stood in the open, made ritual speeches, and then took pride in fighting gracefully. Such behavior became lethal in the presence of peasant soldiers ungracefully blasting away with guns. In addition, guns were a foreign invention and grew to be despised, as did other things foreign in Japan after 1600.” The samurai-controlled government gradually restrict gun production and licenses “until Japan was almost without functional guns” again.

As Jared Diamond says in Guns, Germs and Steel, “Firearms reached Japan in A.D. 1543, when two Portuguese adventurers armed with harquebuses (primitive guns) arrived on a Chinese cargo ship. The Japanese were so impressed by the new weapon that they commenced indigenous gun production, greatly improved gun technology, and by A.D. 1600 owned more and better guns than any other country in the world. But there were also other factors working against the acceptance of firearms in Japan. The country had a numerous warrior class, the samurai, for whom swords rated as class symbols and works of art (and as means for subjugating the lower classes). Japanese warfare had previously involved single combats between samurai swordsmen, who stood in the open, made ritual speeches, and then took pride in fighting gracefully. Such behavior became lethal in the presence of peasant soldiers ungracefully blasting away with guns. In addition, guns were a foreign invention and grew to be despised, as did other things foreign in Japan after 1600.” The samurai-controlled government gradually restrict gun production and licenses “until Japan was almost without functional guns” again. Contemporary European rulers also included some who despised guns and tried to restrict their availability. But such measures never got far in Europe, where any country that temporarily swore off firearms would be promptly overrun by gun-toting neighboring countries. Only because Japan was a populous, isolated island could it get away with its rejection of the powerful new military technology. Its safety in isolation came to an end in 1853, when the visit of Commodore Perry’s U.S. fleet bristling with cannons convinced Japan of its need to resume gun manufacture. That rejection and China’s abandonment of oceangoing ships (as well as of mechanical clocks and water-driven spinning machines) are well-known historical instances of technological reversals in isolated or semi-isolated societies. Other such reversals occurred in prehistoric times. The extreme case is that of Aboriginal Tasmanians, who abandoned even bone tools and fishing to become the society with the simplest technology in the modern world. Aboriginal Australians may have adopted and then abandoned bows and arrows. Torres Islanders abandoned canoes, while Gaua Islanders abandoned and then readopted them. Pottery was abandoned throughout Polynesia. Most Polynesians and many Melanesians abandoned the use of bows and arrows in war.

Cristóvão da Gama, the son of Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama, also fought a Muslim Jihad in Ethiopia in support of local Christians with harquebuses during the 1540s. Within a mere decade of seeing this weapon for the first time, the Japanese were mass producing them on their own, and they soon had more guns than any European army, including great power Spain, did at the time. The fact that this was later suppressed shows that there can be powerful social factors resisting change in any society, but the Japanese had certainly demonstrated a remarkable talent for innovation and adaptation.

The Japanese were afraid of an invasion by Spain or Portugal, which was not entirely unfounded given that they had recently conquered large areas in the Americas and the Spanish had a foothold in the Philippines in Southeast Asia, ruled as one of the territories of New Spain. They were also annoyed at the spread of Christianity which accompanied the European newcomers, and the authorities finally expelled Catholic missionaries and executed a significant number of Christians.

During a period of self-imposed relative Japanese isolation from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, Nagasaki was maintained as the primary window to the outside world. Western sciences were called Dutch Learning, since trade was largely in the hands of the Dutch, one of the most technologically and scientifically advanced Western nations of the time. Much of it was eventually translated to Japanese and published in numerous books.

The invention of woodblock printing during the Tang dynasty in China (around the seventh or eighth century AD) was intimately linked to Buddhist monasteries and art. Stamped figures of the Buddha marked the transition from seal impression to woodcut. Buddhism came to Japan via Korea and China, and monks brought with them, in addition to tea and thus the basis for the elaborate Japanese tea ceremonies, other aspects of Chinese civilization, among them printing. Yet this invention remained tied to religion for a long time. Until the sixteenth century, at roughly the same period as they encountered Europeans, the Japanese printed only Buddhist scriptures.

The invention of woodblock printing during the Tang dynasty in China (around the seventh or eighth century AD) was intimately linked to Buddhist monasteries and art. Stamped figures of the Buddha marked the transition from seal impression to woodcut. Buddhism came to Japan via Korea and China, and monks brought with them, in addition to tea and thus the basis for the elaborate Japanese tea ceremonies, other aspects of Chinese civilization, among them printing. Yet this invention remained tied to religion for a long time. Until the sixteenth century, at roughly the same period as they encountered Europeans, the Japanese printed only Buddhist scriptures. According to the book Technology in World Civilization — A Thousand-Year History by Arnold Pacey, “Printing has been stressed here because the ready availability of books was a stimulus to the growth of habits of abstract thought, often analytical, in China and Japan as much as in the West. But while there were many seventeenth-century Europeans who applied such analysis to problems of map-making or mechanism — to wheels, levers and chemical substances — in China, people with the same inclinations applied them instead to the analysis of documentary evidence or linguistic problems.”

Some Europeans arrived in China during the late sixteenth century, among them the Italian missionary Matteo Ricci. At this time, the printing press invented by Gutenberg had been turning out large amounts of printed material in Europe for a century and a half. Still, Ricci commented on the sheer number of books that were available in China, as well as their low prices. Even though book printing had been operating in China for at least eight centuries, the content of these books did not always favor science or technology. The more decentralized book trade in Europe had been concentrated around the universities from an early age, a kind of institution that did not have any real equivalent in China. This gave it a different direction.

Some Europeans arrived in China during the late sixteenth century, among them the Italian missionary Matteo Ricci. At this time, the printing press invented by Gutenberg had been turning out large amounts of printed material in Europe for a century and a half. Still, Ricci commented on the sheer number of books that were available in China, as well as their low prices. Even though book printing had been operating in China for at least eight centuries, the content of these books did not always favor science or technology. The more decentralized book trade in Europe had been concentrated around the universities from an early age, a kind of institution that did not have any real equivalent in China. This gave it a different direction. Consequently, “by 1601, when Matteo Ricci, a Jesuit priest, presented a European clock to the Chinese emperor, the literary and agricultural emphasis of Chinese culture was so strong that, as Ricci noted, nobody with real ability took up mathematics, and no new work was being done. The great clocks made before 1100 no longer existed, and the thinking behind them had been forgotten. So the European clocks which were now being introduced were not recognized as symbols associated with cosmological ideas. They were collected along with other mechanical novelties as ‘intricate oddities’. The Chinese writer who used this phrase added that they were ‘attractive to the senses’, but ‘they fulfil no basic need’.”

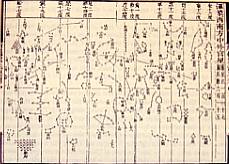

In many societies, astronomical work was an important stimulus behind dissemination of ideas about mathematics, clocks etc. In China, the emperor claimed to have a Mandate from Heaven, which meant that interpreting the heavens was important for the legitimacy of the dynasty. Maintaining a precise calendar was also crucial for running the daily lives of his subjects. Astronomy thus had a political significance.

In the eleventh century, the polymath Su Sung rose to prominence through the bureaucratic examination system and did work for the Imperial Bureau of Astronomy. His star maps are considered among the oldest ones ever made in printed form. He is remembered for his large, water-powered astronomical clock tower, completed in Kaifeng in 1094 on the emperor’s orders. However, although it was the most advanced piece of clockwork created to date, it was a government-sponsored project. When the imperial court lost interest, it wasn’t followed up. Nomadic invasions, first by the Jurchens of the Manchurian-based Jin Dynasty in the twelfth century and then by the Mongols in the thirteenth, also disrupted these developments.

In the eleventh century, the polymath Su Sung rose to prominence through the bureaucratic examination system and did work for the Imperial Bureau of Astronomy. His star maps are considered among the oldest ones ever made in printed form. He is remembered for his large, water-powered astronomical clock tower, completed in Kaifeng in 1094 on the emperor’s orders. However, although it was the most advanced piece of clockwork created to date, it was a government-sponsored project. When the imperial court lost interest, it wasn’t followed up. Nomadic invasions, first by the Jurchens of the Manchurian-based Jin Dynasty in the twelfth century and then by the Mongols in the thirteenth, also disrupted these developments. By the time Europeans made their presence felt in the region, though water clocks were used in China and India, “Japan was the only Asian country where clocks of the western type were being made in the seventeenth century, and where new designs evolved.” Just as with guns, the Japanese saw the potential in European mechanical clocks before any other Asians did.

As Pacey says, “In Japan, the adoption and development of technologies transferred from the West may seem to have begun abruptly soon after the Meiji Restoration of 1868. However, the reality is that Japan was able to use those technologies effectively because a technically innovative culture had been evolving for a long time. This had been stimulated by a selective adoption of western techniques since the sixteenth century, and by a much longer tradition of borrowing and developing technology from Korea and China.”

The Tale of Genji, written by the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu in the eleventh century, is considered one of the masterpieces of Japanese literature, and a testimony to the fact that Japanese culture could create works of great beauty before the modern era. However, during the ensuing “feudal” centuries and samurai period, powerful families and warlords, or shogun, ran the country, with the emperor usually as a figurehead. Following the Meiji Restoration ending the Tokugawa shogunate, a centralized government with the emperor (or an oligarchy around him) as its focus was established. The samurai class was abolished and crushed. A modernizing civil service emerged, with institutional changes in banking and company law. This modernization was partly paid for by the continued poverty of peasant farmers.

The Tale of Genji, written by the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu in the eleventh century, is considered one of the masterpieces of Japanese literature, and a testimony to the fact that Japanese culture could create works of great beauty before the modern era. However, during the ensuing “feudal” centuries and samurai period, powerful families and warlords, or shogun, ran the country, with the emperor usually as a figurehead. Following the Meiji Restoration ending the Tokugawa shogunate, a centralized government with the emperor (or an oligarchy around him) as its focus was established. The samurai class was abolished and crushed. A modernizing civil service emerged, with institutional changes in banking and company law. This modernization was partly paid for by the continued poverty of peasant farmers.The dark side of this was the rise of a militaristic Shinto religion, the native Japanese religion but purified of Buddhist, Taoist and Confucian elements and promulgated by the state to shore up its support and strengthen Japanese national unity. Shintoism was again reduced to a private, personal faith, as it had originally been, under the leadership of American General Douglas MacArthur following Japan’s defeat in the Second World War.

As Arnold Pacey says, “Undoubtedly, the greatest of all Japanese industrial skills inherited from before the Meiji period were those relating to organization and commerce, and these skills were clearly demonstrated by the way in which the introduction of new technologies was managed.”

Moreover, “despite the many reforms, there was also an important element of continuity, notably in the strong merchant class. For example, the Mitsui firm dated back to 1683. There was also continuity in technology, both with respect to the long-standing Japanese interest in western techniques, and in the persisting importance of traditional technology and local innovation. It will be recalled that from the 1630s, Japan had limited its trade with the West to one small Dutch trading post. In 1720, the import of European books was liberalized. A number of scholars learned Dutch and studied medicine, agriculture and other technical subjects from the imported literature. Translations were authorized and circulated widely in this highly literate society. By 1820, there were schools of ‘Dutch studies’ or western knowledge, and a handful of young men were being quietly sent abroad to study western technology.”

By 1905, “Japanese raw silk exports equalled China’s and supplied one-third of the world market. Soon after, Japan overtook China and became the biggest supplier to countries such as France which had large silk-weaving industries. Although improved silk-reeling machines played a part in this expansion, the more crucial changes were associated with improvements in organization rather than technique. There was better quality control through a government system of licensing producers of silk-worm eggs, and large-scale marketing of the product was undertaken by firms such as Mitsui.”

Moreover, “The employment of foreign technical advisers was also very carefully organized. In particular, all their costs were paid by the Japanese so there would be no doubt about who was in control. One of the largest groups of foreigners were the British railroad engineers and managers working under William Cargill, who was director of railways and telegraphs from 1871 in partnership with a local man, Inoue Masaru. The British supervised the building of the first railroad in Japan, the Tokyo-Yokohama line, which opened in 1872.”

After 1881, “Japanese railroads continued to depend on imported rails and equipment (until after 1900), but foreign engineers were called in only when major bridges were designed. Railroads and shipyards were encouraged particularly strongly by the government in Japan, and considerable subsidies went into these two industries between 1868 and 1913.”

With the rapid expansion of scientific and technical education, “foreign teachers were employed, mainly at Tokyo University, which was founded in 1877. But Japanese teachers were so quickly trained that by 1893 there were no foreign professors left.”

Japan also embarked on creating a colonial empire of its own. Pacey again:

The western powers prevented a full Japanese take-over in Korea until 1910, but Taiwan became a colony, and Japanese goals in Korea were pursued by buying up its first railroad, which had been begun by American engineers in 1896. (…) Russia had not only built a railroad across Manchuria (part of China) to reach Vladivostok, but had leased the Chinese ports of Dalian and Lushun (‘Port Arthur’). These had been connected by railroad with the Russian system, and considerable numbers of troops were employed guarding the lines. Fearing further Russian consolidation, the Japanese attacked ‘Port Arthur’ and in 1905 defeated the Russians both there and at sea. Under the treaty which followed, they took over the port and its railroad connections, and formed an organization known as the South Manchurian Railway to run them. This became the main agency for Japanese economic penetration of this Chinese territory, and was particularly important in giving access to iron ore reserves, shortage of which had been a considerable disadvantage to Japan hitherto.

China experienced a period of unrest and civil war in 1852-60 and was subject to foreign invasions. There were attempts to modernize, but these “depended heavily” on engineers from Western countries. The Chinese “were also limited by the way in which ‘self-strengthening’ policies were conceived only in terms of acquiring technology and technical education. There was no recognition of the need for new forms of organization to make the new technologies effective, and thus there were no institutional reforms like those in Japan after 1868. One result was the chronic difficulty in raising capital for new projects and arbitrary taxation of profits.” The extra-territorial rights for traders from Western countries established after the Opium Wars, a less-than-proud chapter in Western history, didn’t help, either.

During the time of the Han dynasty in China (206 B.C. to 220 A.D.), Japan imported iron and bronze-making, rice farming and other ideas with migrants from the Korean Peninsula and China. By the sixth century A.D., Chinese characters dubbed Kanji or “Han characters” had become widespread. There was no writing system in Japan prior to this. In modern Japanese, Kanji has been combined with two other systems, hiragana for words for which no Kanji exists and katakana for words from foreign languages, to make up written Japanese. During the sixth and seventh centuries, the Baekje kingdom in the Korean peninsula and the Tang Dynasty in China brought philosophies such as Buddhism and Confucianism to Japan.

In light of these examples, it would be tempting, but not entirely accurate, to say that Japan was to China what Western Europe was to the Byzantine Empire. Some regions of Western Europe did once belong to the same political entity as Byzantium, which Japan never did with China. Also, the Japanese relationship with China (and Korea) is highly complex. Japan the apprentice attacked China the master, and many Chinese and Koreans are still angry over Japanese war policies in the twentieth century. They behaved at least as badly in Asia against the civilian population and Allied prisoners of war as the Nazis did in Europe. Many Chinese also tend to dismiss Japan as a slightly inferior copy of China. This isn’t fair, but it is true that Japan has borrowed heavily from China in the past and that no Japanese can deny this.

No major civilization exists in total isolation. Byzantine glazed ceramics developed, beginning in the seventh century, “based in large part on models from Persia and even China. A thriving industry in ceramic production developed with many regional centers and different styles.” In some periods like the Tang dynasty, outside influences (above all from India) to China could be quite substantial. However, in the long line of history, China has indeed been more self-sufficient than Japan, and was probably one of no more than a handful of cultures on earth to invent writing independently. China could thus make a legitimate claim to be the center of the world. Japan could not, precisely because it was next door to China.

Japan is different from the West in some very important respects. Japan does not share the Western notion of universalism or the same strong feelings of guilt for its colonial history. Some observers have suggested that this is due to the absence of Christianity, which means that concepts like original sin and the global brotherhood of man find little cultural resonance there. The Japanese have remained largely insulated from the “diversity” problems of the West. They obviously don’t copy anybody slavishly, yet are flexible enough to adopt good ideas from abroad while still sticking to the core of their cultural traditions.

Despite many obvious differences, perhaps there was a defining trait that Western Europe did share with Japan: They were both, strictly speaking, upstarters and latecomers, and could make no claim of being the original seat of civilization when compared with their far older neighbors. Perhaps this cultural secondarity gave them a flexibility that the older civilizations lacked. The Japanese were thus the first people in Asia to take up the challenge from the West because in some ways, they were most like the West. It now looks as if China is making a determined effort of making up for lost time. Only time will tell if they will succeed.

Western Europe in the early modern age was unusually apt at both innovation and at improving inventions imported from abroad. They met their match in the Japanese. Whatever the cause, it is a fact that the Japanese have performed remarkably well at innovation and at making outside inventions even better, assimilating them and improving them during a remarkable short period of time. This remains as true in the twenty-first century as it was in the sixteenth.

9 comments:

Superb essay, Fjordman. Thanks!

With the calibre of posts, and comments for that matter, that GoV gives and gets, it's no wonder it's a smaller blog than the borgswarms of the net. There aren't all that many smart folks in the world.

I suspect the influence of this blog on western academic opinion is more profound than the c/p of some of the larger blogs.

The Byzantine empire did not evolve as did the West into the scientific-industrial greatness precisely because it was never destroyed, as was the West.

What existing order remained in the West was fragmented and weak; there was little to hold back the evoluton of a new culture based on a fresh look at the old.

Sorry xlbrl but I do not agree with you at all.

First, the West was never really destroyed. The Roman Empire collapsed, but it was all.

The Germanic peoples going South rapidly recognized their "inferiority" and thus, despite becoming the ruling elite, they adopted the ways of the Celto-Roman peoples they conquered.

They rapidly assimilated into the people and became part of the people. It happened in Portugal, Spain, Italy and specially France. In the U.K. the same happened but with all its specifications, minly because Britain is an island.

That's why in the Latin West (and maybe the Germanic as well), during the V century there was the following popular expression:

"A rich Goth's dream is to became a Roman, the poor Roman's dream is to became a Goth"

The Western Empire was never destroyed, that's why if the Visigothic and Ostrogoth kingdoms union had lasted, Southwestern Europe would still being the world's leading power, and Portuguese, Spaniards, Italians and Southern French would still be speaking Latin. In where I live, in the extreme West of what once was the Roman Empire, in the province of Hispania, Latin was the official language until the XII century. Hispania was for 8 centuries islamic, but the Christian North was always proud of being "Roman" even after the empire had collapsed. Actually even in the South, muslims were never more than a tiny minority being a majority only in some big cities and "Romanity" was a comfort to the dhimmi majority South which was best expressed in Catholicism and obidience to the "White Roman Emperor" (aka, the Pope.)

Byzantium otherwise was destroyed in 1453 and it became the Turkic gateway to Europe. 29th May 1453 was the day when Constantinople felt but the Empire was being destroyed ever since.

Though, the Byzantine Empire was always THE major European power and heir of Rome itself, it felt when the rest of Europe standed tall and proud. That's why the West needed so badly a leader as Charlesmagne (Carlos Magno in Latin) revealed himself to be. Though, too weak if compaired to Byzantium.

The thing is, the Roman Empire collapsed in the West but was destroyed in the East five centuries later.

Fjordman said or implied:

"The two most threatening others to Europe were the muslims and the Byzantines"

What really hapened is that, once we take Europe as a very large family, Byzantines were never the others. The muslims, turks, mongols or arabs were others but Byzantines were the younger brother who got the crown that should belong to the older brother - The West.

So, that's why de West were hostile at Byzantium. The father (Rome) should never had favoured the younger brother.

In that sense we can see that the Jews are like a mother-in-law that we want to get rid off.

Americans are the "black-sheep" the rebel son that we never saw as someone capable of doing things right but who can now "lead the company" better than us.

I think you Americans should focus on that.

This article has been submitted to StumbleUpon. I would like to encourage other StumbleUpon members to give it a thumbs-up and an additional review. This article deserves wider attention.

sorry you are sorry, henriques--

the existing civilization in the West was destroyed. I did not say by whom, or what. It may be that a larger factor than the collapse of Roman order was the ten year absence of growing seasons in the sixth century, particularly severe in the North. Whatever the case, it was not called the Dark Ages for nothing.

Then there would be in time no central authority strong enough to keep the various cultures and languages from evolving with and against themselves, not even the Church.

That would not be true in the old Byzantine Empire, where Islam would work it's magic.

xlbrl,

"the existing civilization in the West was destroyed"

I don't think so. It is like a brotherhood. Celtic, Germaic, Italic, Greek, Slavic cultures, among others, were very similar one to another. The differences and specifications are the essence of the West or Europe. It all started there. Rome was the unifyer of all that and created, in my view, a common ground to Europe (but Slavic and Germanic Europe) that spread then to the Germanic North during the Dark Ages.

Actually, dark ages were an ephoque in "Western" (European) history where the Roman (European) vallues were being atacked:

Huns were defeated, rapidly in Hispania the Moors conquered too many land, and the Vikings and other Germanic barbarians were atacking the "West". In the East Turks and Arabs were damaging as well. The Dark Ages are, in my opinion, a time when Europe was at risk, threatened by non Europeans from every corner (the Mongols would be next) and even by the European baribarians from the North. As the "Northern Barbarians" were civilised the Dark Ages ended and the "Middle Ages" started. It's difficult to get ahead with this new aproach. When did the Dark Ages finished and the Middle Ages started?

It differed from region to region and to some, there were no "Bright Middle Ages".

So, I guess the West was never destroyed, it was seriously threatened but it survived. (Southern France(?),) Portugal, Spain and specially Italy are so heirs of Rome as the Greeks are the heirs of Bizantium.

Bullfights and Soccer are the modern equivalents of the gladiators, for exemple.

The West did, in fact survived without Rome, will it survive with this modern chalenges?

Sorry, Mr. Henriques, but archaeological evidence shows that civilization in the western Empire was largely destroyed in 400-600 AD. The quality of manufactured goods declined sharply and entire classes of goods disappeared completely. Many cities and towns were destroyed and never rebuilt. Buildings were abandoned. Large tracts of cultivated land reverted to wilderness. The population crashed by about 50%.

Elements of the classical civilization were passed on, but the civilization itself was smashed.

I apologize for the lateness of this comment as I only discovered this blog a few days ago and am currently reviewing the archives.

I can't remember any of the titles of works that I used for research on this subject, but it's worth noting that Japan (or the Japanese) did initially embrace Christianity with great fervency when introduced to it by St. Francis Xavier and others in the 15th Century. It was only after Tokugawa Ieyasu consolidated power that the persecution began in earnest with hundreds of thousands of Christians suffering martyrdom as the country closed itself off to the western powers. Apparently Christianity was a sign of "weakness" - particularly in the Samurai culture. Strangely enough, even today, Japanese popular fiction/culture presents a very weird, distorted view of Christianity, both now and in the historical context.

Wish I could recommend some good book titles, but they all escape me at the moment.

Post a Comment