Ninety Years On

Last year I wrote a series of posts featuring the poetry of the Great War, and concluded with poems by two British soldiers who survived the War. Now it becomes necessary to revive the series in order to add a coda with song from Al Stewart’s latest CD.

It had seemed that the magnificent work in Between the Wars (1995) might well be the capstone of Mr. Stewart’s career. Down in the Cellar, which came out in 2000, is a pleasant enough CD, a themed collection — every song is about wine or vintners — but it doesn’t rise to the level that Between the Wars attained.

Then came his latest work, A Beach Full of Shells (2005), which indicates that the old man is still at the peak of his form. The song containing the collection’s title is its most powerful, looking back most of a century to ponder the impact of the Great War on the English, and on English poetry.

Then came his latest work, A Beach Full of Shells (2005), which indicates that the old man is still at the peak of his form. The song containing the collection’s title is its most powerful, looking back most of a century to ponder the impact of the Great War on the English, and on English poetry.Somewhere in England 1915- - - - - - - - - -

by Al Stewart

On the platform of an old railway station I enter a dream

And a couple are saying good-bye through the noise and the steam

But it’s just Brief Encounter my mind is trying to rerun

And I wait for the poignant finale but the dream has moved on

And the train has turned into a ship that is sailing away

And the platform is a beach full of shells under silvery grey

And the girl on the beach is an English Prime Minister’s daughter

And she watches the ship disappear at the edge of the water

And it feels like the pain in her heart will be never-ending

And everyone feels this way in the beginning

And she watches the ship disappear for the length of a sigh

And the maker of rhymes on the deck who is going to die

In the corner of some foreign field that will make him so famous

As a light temporarily shines to illumine his pages

Then the scene has changed once again; now it’s moonlight on wire

And the night is disturbed by a sudden volcano of fire

And a skull in a trench gazes up open-mouthed at the moon

And the poets are now Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon

And nobody talks anymore about losing and winning

And everyone feels that way in the beginning

And I’m up in the air looking down at a girl on a bed

She’s lying asleep on her side with a book at her head

And it’s someone who left long ago

Was it something I said?

And I hope that she’s reading “King Lear”,

But it’s “Twelfth Night” instead.

Now the girl and the beach and the train and the ship are all gone

And the calendar up on the wall says it’s ninety years on

I go out into the yard where the newspaper waits

There’s a man on the cover we all know, defying the fates

And he seems very sure as he offers up his opinion

Well everyone feels like this in the beginning

When you feel that the pain in your heart will be unending

Everyone feels this way in the beginning

If you feel that the pain in your heart will be never-ending

Well everyone feels that way in the beginning

Mr. Stewart shows an admirable restraint in the last stanza. It would have been so easy to name the man on the front of the newspaper — Bush, Blair, Osama bin Laden, whoever — and make the song topical and relevant, and earn the plaudits of the bien pensants. But he didn’t go there; he left the topic to our imagination, where it belongs.

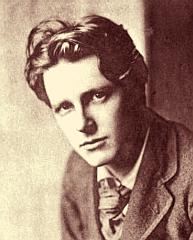

The poet who was made famous by the “corner of some foreign field” was, of course, Rupert Brooke. His poem was the most well-known and popular of the war poems until the mass insanity that was the Great War turned poetical sensibilities in a different direction.

But in 1915, this was the song of the flower of England’s young men:

The Soldier

by Rupert Brooke

If I should die, think only this of me;

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England’s breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

Rupert Brooke personified the English moment that died on the Western Front and was never recovered. Even though Edward VII was dead by then, Brooke exemplified the Edwardian period, when the tide of British power was at the flood, and when the arts in Britain were still burning with their last bright flare before the slide into decadence and narcissism and Modernism.

Rupert Brooke was a pretty boy, a hedonist who had numerous flings with members of both sexes. Curly-haired and dashing in his uniform, he embodied the noble British ideal when he went off to the war. His premature death was a heartbreaker, and ensured his literary immortality. The unromantic details of his death — he died on Easter Sunday, 1915, of tetanus from an infected mosquito bite, en route to the disaster at Gallipoli — could be ignored. He stood for England.

Rupert Brooke was a pretty boy, a hedonist who had numerous flings with members of both sexes. Curly-haired and dashing in his uniform, he embodied the noble British ideal when he went off to the war. His premature death was a heartbreaker, and ensured his literary immortality. The unromantic details of his death — he died on Easter Sunday, 1915, of tetanus from an infected mosquito bite, en route to the disaster at Gallipoli — could be ignored. He stood for England.And then the whole façade came crashing down in the mud of Flanders. Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon did indeed become the poets of the war, and the romantic martial ideal departed from poetry, never to return.

Brooke’s life and death are a bitter irony, compounded by the fact (as Paul Fussell has observed) that it was the horror of the Great War that gave birth to irony in modern Western culture.

Dymphna and I were discussing all this the other night, and she wondered if the looming demographic disaster in Europe might be a result of the Great War, the final consequence of a conflict so horrendous and meaningless that it destroyed the collective will to live of an entire continent.

There’s another Al Stewart song in the latest collection that enlarges the retrospection to include Edwardian times and pan the camera across an entire century:

My Egyptian Couch

by Al Stewart

Now here’s a book full of photographs

That my ancestors made some generations ago

They’re wearing the latest clothes in a nautical way

The Suez Canal close behind is frozen in time

The deck crews stare out of a mime

And they seem to be considering me

Here on my Egyptian couch

O the life on Edwardian steamships

Is measured and slow, while down below

There are fires that shudder and clang and thunder

And sweat-caked in smoke, and cauldrons to stoke

To send the ship on her way

Tasting the salt and the spray

And a century later I scan the equator

From my Egyptian couch

And the news every day brings

Contains the strangest of things

But with confident smiles my forebears decline

To gaze into the wings

So they look from the photographs

And they’re curious now, wondering how we turned out

Let’s say like the Chinese adage

We’re living our lives in interesting times

When I went looking for a First World War image to go with this post, I had to search through websites containing hundreds of Great War photographs. After a while the enormity of the horror was so great that I simply couldn’t look at any more of them — trenches and craters and muddy fields covered with mutilated corpses, body parts in every cubic yard of churned-up mud, bloated horses and shredded clothing and smashed equipment and Death — a little more than a little was by much too much. You could lay all the photos of Great War corpses side-by-side, and they would run from here to Seattle, with plenty of them left over.

We’ve never recovered from the Great War. With the influenza epidemic hard on its heels, the War did damage to Western culture that has not yet run its course. Even those blessed souls who are totally ignorant of its history have to live with its consequences every day of their lives.

As the Great Jihad burrows its way into our countries and our institutions, it enters by the cracks and fissures and gaping holes that are left over from the period between 1914 and 1918.

4 comments:

“Dymphna and I were discussing all this the other night, and she wondered if the looming demographic disaster in Europe might be a result of the Great War, the final consequence of a conflict so horrendous and meaningless that it destroyed the collective will to live of an entire continent.”

Not quite maybe but…

On the personal level:

my paternal grandfather was gassed in France, having fought at Gallipoli. He died at 48. My maternal grandfather was (I think) gassed and wounded. He died (I think) at 45. A paternal great uncle died at 39 (also having been gassed and wounded several times in France and also having fought at Gallipoli). My wife’s grandfathers both fought in WW1. They were not severely harmed but were both (temporarily?) quite badly affected. They both also fought (one dying, along with one of her uncles) in WWII

On the national level:

Here is the table of casualties from Wikipedia:

Table of WWI casualties

A cheery photograph:Ypres

Here are the WW2 casualty figures: Table of WWII casualties

Finally, remember the flu pandemic of 1918/19: estimated to have killed 50 to 100 million people. the flu killed 25 million in its first 25 weeks. In contrast, AIDS killed 25 million in its first 25 years!

Baron

I was hoping in 1989 that the lamps had finely come back on in Europe. But I’m afraid the results of that nightmare will be with us for while.

This is one of your best.

I’m stealing the link for a possible post i was writing for last August but was postponed by events.. Hope you don’t mind.

Hank

Erich Maria Remarque's "The Road Back" is essential reading for an understanding of the effects of the First World War. It's not nearly as well known as his "All Quiet," but I think it's a better and more important novel.

Also, "The Great War and Modern Memory" by Paul Fussell.

Hank -- Steal anything you like! That's what it's there for.

David -- yes, the Fussell reference is from that book (I think). I read it some years agp; an important work.

Post a Comment