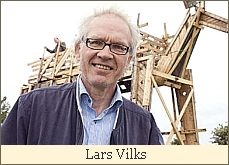

Lars Vilks is the Swedish artist who gained worldwide fame with a series of drawings of the Prophet as a Roundabout Dog. Not satisfied with the outrage caused by mere caricatures, Mr. Vilks recently launched his musical Dogs, which further inflamed the tender sensibilities of Swedish Muslims and the leftists who cater to their every whim.

Lars Vilks is the Swedish artist who gained worldwide fame with a series of drawings of the Prophet as a Roundabout Dog. Not satisfied with the outrage caused by mere caricatures, Mr. Vilks recently launched his musical Dogs, which further inflamed the tender sensibilities of Swedish Muslims and the leftists who cater to their every whim.When Mr. Vilks was in Stockholm for the opening of Dogs, Tundra Tabloids had the good fortune to obtain an exclusive interview with the famous Islamophobe. The interview took place in Central Train Station in Stockholm on November 23rd, a day after the premiere of Dogs, which was part of the “A Day For Free Speech” event. Audio, video, and still photos of the interview are available at Tundra Tabloids.

Here are some excerpts:

| TT: | | …Now first of all, about the event that took place yesterday, could you give me your thoughts or comments on what you hoped to achieve by that…collage of different videos concerning the Mohamed dog cartoon, the roundabout dog, and your answer to your critics? |

| LV: | |  There are many frontiers in this drama, I have one that goes with my main project which is about the art world, and the agenda they have in the art world, and when they do something incorrect, which is very obvious, and I’ve done it just to find out about what is the situation to critique what is the freedom within the art world and this was just one way of protesting, to keep it alive, to kind of follow up with documentation that I’m very well aware of working with this very huge project, as well as everything that happens can be part of the art work. When you make a musical, you make this possible to view. There are many frontiers in this drama, I have one that goes with my main project which is about the art world, and the agenda they have in the art world, and when they do something incorrect, which is very obvious, and I’ve done it just to find out about what is the situation to critique what is the freedom within the art world and this was just one way of protesting, to keep it alive, to kind of follow up with documentation that I’m very well aware of working with this very huge project, as well as everything that happens can be part of the art work. When you make a musical, you make this possible to view. |

| TT: | | Right. |

| LV: | | You make this a part of a summary, in a kind of an amusing form. I mean, I didn’t expect, and I do not expect, because I haven’t seen any of the reactions yet from that point of view, but I think that it’s too early to have some sort of communication with the art world. So this is an ongoing thing. I have to wait I mean, and that’s the point I think, if it went to fast it wouldn’t be so serious. |

| TT: | | Right. |

| LV: | | When you crash into some sort of institutional critique and you’re really serious about it, then you, I mean, either you do something which is totally stupid and impossible, or otherwise you really hit the nail and then you have to wait to see what happens. That’s one thing, the other thing of course is what goes on in the world. The world is also fascinated by this, I mean really, it’s mostly with the Arabs with things going on. And that went all right. It was the first bloodshed we had yesterday? |

| TT: | | Oh yeah… |

| LV: | | It was the first bloodshed? |

| TT: | | Yes it was. |

| | | [The Local: When Vilks stood to address the several hundred people gathered in the ABF building in Stockholm, a young woman rose to her feet, made threatening gestures with her key ring and screamed at the artist. One of the debate’s organizers seized the woman in order to escort her from the premises. “She then scratched her keys over his underarm, cutting him in two places,” said Filip Björner for the event’s organizers, the Swedish Humanist Association.] |

| TT: | | Ok, now for our viewing audience here, could you please take us through the history of what led you to draw the Mohamed dog cartoons? |

| LV: | | Yeah. It’s rather trivial story which I think is important because people mean that I had an aim to put a political issue behind it, but that was very limited, very limited, because the only thing that I was interested in was, to do something which is not allowed in art, and that is to criticize Islam, come up on the Muslims side, while you can of course criticize terrorists, United States and terrorists, and things like that which is normal to do. So, but this was a very small exhibition, the theme of a dog in art. So I should do something with a dog, do something to provoke with dogs, such as with a prophets head on that dog. |

| | | I mean, that wasn’t too much if you understand that this was such a small place and probably nothing would have happened there if the curators hadn’t take the position to suddenly, suddenly censor it in the last moment, when they already had them hanging up on the walls and then they took them down, and then the press was there, they actually got the news of the controversy and it was spread in the wind. So that’s how things got started to move outside, and then came of course all the stories about how sly I had been, that I had a plan you know, to plan these things, [laughter] |

| TT: | | What has, in your own personal opinion, been the public’s reaction to the dog cartoons here in Sweden? An overall view. Has it been entirely negative, eh positive? From the event held yesterday, I, we saw first hand the critics, and your answer to the critics in the short videos, what is your overall viewpoint concerning Swedish society and how they have taken your display of this cartoon? |

| LV: | | Yeah, I’ll say that there has been of course defenders of these things, defenders of the freedom of speech, and then you have the other criticizing that you are attacking a weak group which is an immigration problem, and things like that. I think there’s a basis, it should be fair to say that there are more criticizing that are supporting. But it’s not totally unbalanced, it’s not totally unbalanced, it’s a rather reasonable unbalance, but the strong forces are of course those who are criticizing because they are standing on the political correct, political correctness already, and so, but I mean all these things is of interest to me because then I’m kind of am mapping, because I came as a newcomer into this, this countryside, and I can kind of see all these different camps and how they attack each other and what sort of arguments they use. |

| | | […] |

| TT: | | But what about from outside of Sweden, support, where has it been coming from? |

| LV: | | Well from all parts of the world. |

| TT: | | Have you been surprised by it, or expected it? |

| LV: | | Well, when it went out in the world like that it was of course unexpected, but when that happens, I mean, I can understand that the question is interesting and that many people are concerned with it. I can see that groups that are working for freedom of speech and against political correctness in many parts of the world, so, so, I mean on the air, several countries small and big radio stations, and things like that have been used in the discussion. I mean, it’s very similar everywhere, you have kind of, what you can, what you cannot say, what is correctness. I mean it’s about the same everywhere. |

| TT: | | What kind of mark would you give the academic community, your peers, concerning their reaction to the drawing of the cartoon? From A to E being the worst? If you could grade them on their overall reaction to this. |

| LV: | | Well they did what they should. They are standing for something and they are representing something, and that was the idea of my project. I mean was going to show how is the agenda and how are the conventions, in the freedom of art, where everything today said is possible to do anything, and actually we have a problem because everything is done and can’t provoke anything more. And I had the idea that it’s very easy to provoke, you just need a small dog. |

| | | […] |

| TT: | | Has anyone been able offer a credible counter argument against the publication of the Mohamed Roundabout dog cartoon? In other words, has any voice that you have noticed that has tried to be intellectually honest from their prospective, to say that it wasn’t something wise to do? What would you have to say to that type of criticism? |

| LV: | | It’s very common to say, it’s unnecessary provocation, but again, you have to remember the circumstances. When did it become something? It became something when the day the censorship came in, and the publication became something, and probably I would have been doing the same thing even if I knew that, because when you do something, if it’s bad it’s more interesting because it has another effect. So I mean, there is no doubt, that when you do something as an art, as a work, deliberately, you can take an art, it is by tradition much wider than in ordinary life, it’s just not a political issue, it’s kind of an aesthetic issue where you have the borders, an art is about offending and insulting really, it’s a history of provocations. And you transgress borders of things or another so, it should be quite an ordinary thing. |

| | | […] |

| TT: | | How can other do that you have done, preserve free speech by using it to criticize sharia law and what should we prepare for if we do? |

| LV: | | It’s a holy area about Islam in the art world, so there is still things to be done. I mean, to make this kind of a conventional critique which it should be, you criticize Christianity or whatever you do, I mean so it should be also be possible to criticize Islam in that sense. So a, we can see that these things have been done, they are not pushed away. |

| TT: | | I believe that I already know the answer to the question before I even ask it, but since I have it here I will, do you have any regrets over the drawings whatsoever? |

| LV: | | No. And I don’t think that the project is at the end, I mean it’s still alive, I mean you could see yesterday that it’s still alive, it has not settled, the project could be shown, I guess that it could be shown a fragment of it, and it became a heavy discussion. There is still a boycott in the art world for the project and all these things are showing that this is still a process, another chapter in the story taking place yesterday. |

| | | […] |

| | | I see this as part of the art work, and I think that it’s more interesting than people just sitting still. Passion, feelings, creating opinions, people believing they’re right. They believe that they understand what I was doing, so I understand all that, I have seen it before, you talk about the artist but he’s not here, the artist is something that we construct together. It’s always a fiction, that the artist is the one who has intention with a work and that is the construction you make. To say that the artist meant this, meant that, and so on, so it becomes something else to the person himself. |

Read the rest of the interview at Tundra Tabloids.

For previous posts on Lars Vilks and the Roundabout Dogs, see the Modoggie Archives.

2 comments:

With a little exhibition of fatwas it would be made clear that it is illegal to stay for the muslims in our lands according to the muslim law and those who stay here in spite of that should be currently termed as muslims-islamophobes.

Imagine an exhibition:

What is fatwa?

The short history of fatwa

Photogalerie of prominent fatwamakers

The fatwas against those who reside in infidel lands

These people are here illegally according to their own faith!

They should not bring with them their qurans either out of religious fear cause those books might become a matter of infidel discussions. Which is going on!

Lars Vilks:

No. And I don’t think that the project is at the end, I mean it’s still alive

Yes the project is still alive! Why don't you join in?

Join the art project!

Lars Vilks:

I see this as part of the art work, and I think that it’s more interesting than people just sitting still. Passion, feelings, creating opinions, people believing they’re right.

Post a Comment