Father’s Day is a pale feast compared to what we do in May for mothers. That’s understandable since mothering roles have changed less than fathering has in the last generation. The daddy template is broken, or if not broken, certainly skewed and bent by stress. As the job has become more thankless and more easily taken from them, fewer daddies are to be found at their posts.

The easiest piece to see of this sad situation is the animus that the previous generation’s feminists have for men. Their anti-male bias has taken its toll on men, but it has not served women well either. Feminist politics are those of resentment and victimization. The younger generation of women coming along behind them are not eager to trap themselves in this ghetto where men are vilified and condescended to.

The most damaging thing the feminist movement did to women was to push fathers to the periphery. “I’d-rather-do-it-myself” was a mantra whose end result was not stronger, happier children. Long term studies of the children of divorce do not paint a pretty picture.

In contrast to this philosophy, I offer two anecdotal pieces of evidence of the importance of fathers for girls. We know they’re crucial for boys if they are to grow up able to strive and to maintain themselves in the world as productive adults, able — as Freud said — to work, to love, and to play. Without Dad, some of that will wither. What about the girls, then?

Here are two stories that show what a woman can only accomplish with the help of her father. These are fathers who had to buck the culture to give their daughters what they needed. They are brave and courageous and anonymous men who deserve our attention on Father’s Day.

The first story appeared this week in the print edition of the Wall Street Journal. Neo-neocon reports the serendipitous appearance at her front door of a copy of the Journal which contained an article entitled “Married at 11, a Teen in Niger Returns to School,” with Roger Thurow's byline. Neo-neocon relates the sad story she read of the young Muslim girls of the Southern Sahara who face several horrific problems directly related to gender.

The first is genital mutilation. The second is premature marriage at wholly inappropriate ages to men much older than they. These early marriages result in pregnancy in little bodies that are not yet ready to bear babies to term. When the babies are ready to be born they cannot easily leave a womb which has no room to let them pass. The result is protracted labor in which long days of pressure on the walls of the uterus cause it to tear a hole between the uterus and vagina. The result is a fistula. The result is urinary incontinence and social ostracism for smelling so bad.

The girl under discussion here was sold by her father into marriage in exchange for a camel. Mr. Thurow gives us her story:

Anafghat Ayoub left school in third grade to get married. Her mother had died, leaving her goat-herder father with several daughters, of whom Anafghat was the oldest. After marrying, Anafghat’s husband left to find work in Libya, but not before impregnating his eleven year old wife. When the baby was ready to deliver, Anafghat’s body was not. She had been in labor for three days when her anxious father scraped together money from friends and relatives to get to the nearest maternity hospital. After traveling over sixty miles of rutted roads they were told the nurses couldn’t handle her delivery.

Mohamed Ayoub hired another car to get to Niamey — another forty dollars and another hundred miles away.

Eventually, the stillborn baby was delivered by forceps but the damage to Anafghat had been done. She had a fistula “the size of a baseball.” The doctors cured her infection, but they could do nothing for the fistula. Anafghat lived at the hospital for four months, waiting the arrival of volunteer American doctors who would be returning for their sixth visit to operate on little girls like her. In the end, a surgeon from Johns Hopkins performed the repair.

Now Anafghat is back in school. She lives at home with her father and sisters and will not be returning to her husband. She plans to go on with her education: while at the hospital she met a woman who is a medical student from Niger. Anafghat decided then and there that she would go on with her education and become like this woman.

Her father agreed with her plan and now all his daughters are with him, and all are in school. The future looks hopeful for this particular family because this particular father allowed his love for his daughter to transcend the limits of his life. The daughter he sold for a camel (which was later stolen) will be the jewel of his family and the way out for his other daughters.

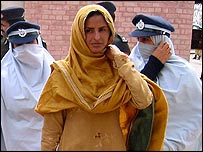

Thousands of miles from Niger there is Mukhtar Mai. Gates of Vienna has devoted several posts to her situation — being gang-raped while her village laughed and danced, her efforts to bring her assailants to justice, her desire to make a better life for the children of her village, the outpouring of aid from around the world in response to her story of courage and determination, even in the face of death by her assailants and their defenders.

The opening chapters of her story are not that different from many tragedies for Muslim women. Shari’a law allows families to sacrifice women for debts of honor and she was thus designated by the village to stand in for a trumped-up charge against her brother. It was the middle chapter when she changed the story line. Instead of leaving to commit suicide as she was expected to do she was met on the road by her father, who covered her nakedness with a shawl and led her home. Through the following days of darkness it was her father and her imam who encouraged her to live, and then insisted that she file charges against her assailant.

And so it came to pass that instead of skulking off to die, Mukhtar Mai went to court. Her assailants were found guilty and she was awarded compensation. She took the money back to her village and opened two schools, one for boys and one for girls. She named the one for boys after her father.

Her story isn’t over yet. President Pervez Musharraf won’t let her leave Pakistan because her story will bring shame on his country. But he is keeping her alive. And money has poured in from around the world, allowing her to bring electricity to her village and to fund other schools. None of this would have been possible without her father’s love and his courage to stand up to the powerful clan in his village who savaged his daughter. Can any of us imagine what it must have taken for this man to shield, protect, and urge his daughter on to justice?

Her story isn’t over yet. President Pervez Musharraf won’t let her leave Pakistan because her story will bring shame on his country. But he is keeping her alive. And money has poured in from around the world, allowing her to bring electricity to her village and to fund other schools. None of this would have been possible without her father’s love and his courage to stand up to the powerful clan in his village who savaged his daughter. Can any of us imagine what it must have taken for this man to shield, protect, and urge his daughter on to justice?These are stories of fathers that could not have been told about mothers. It is not that we don’t love our children. Of course we do. It is that we cannot provide the same things a father can, that a father must provide if he wants his daughter to grow strong and straight.

In this country, you can tell the girls with good fathers. They are at ease in the world and they are confident of finding their way. Unlike the fatherless ones, or the ones with absent or empty fathers, they do not have to live in a city of one. Having experienced being carried by the strong daddy who strode so easily past the white water places where she knows she could have gone under had it not been for him, the girl with the good father is free, freer than she could ever know.

2 comments:

I was blesed with a good father. I always recognized that blessing.

I got to know my father in a different way when my mother unexpectedly died some ten years before my Dad. In those years, I got to know my father, adult to adult. We had great times as long as his health permitted, and his health was good up until that last two years.

I miss Dad every day, now that he's gone. I miss Mom, too, but it's a different kind of absence. Also, I count as a blessing that my mother passed away first because, otherwise, I'd never have had the chance to know my father so well.

Your last paragraph is a gem--and true.

Thank you for this excellent commentary.

I've always thought that one of the more important reasons that girls need good fathers is because their father is their template for the future of what to expect from the men they have relationships with.

We have definately shortchanged our children by entertaining the notion that the father is an archaic tradition.

Post a Comment