My acquaintance with the nature of Islamic fundamentalism began thirty years ago when I first read Among the Believers: An Islamic Journey by V.S. Naipaul. I’m now in the process of rereading the book, just to see what it looks like after sitting through ten years of Advanced Jihad Studies.

It’s an extraordinary book. Mr. Naipaul understood the Islamic revival long before any of the rest of us had even thought about it. And he managed this simply by traveling to Islamic countries and talking face-to-face with Muslims. He listened carefully to what they said to him, and took them on their own terms.

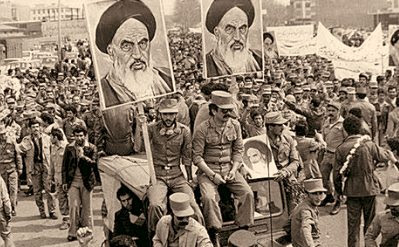

His first stop was Iran, in the summer of 1979, a few months after the Islamic Revolution. At that time the leftists had not yet been entirely eliminated from their prominent positions in the new government and society. Some of the purges of communist groups and publications took place while he was still in the country.

The following excerpt is from the end of Section I, pp. 81-82, just before the author flew from Tehran to Karachi. Behzad is the young Iranian communist who acted as Mr. Naipaul’s guide and translator while he was in Iran:

The plane that was to leave at 7:30 didn’t arrive until 10:00. We began to taxi off at 11:25 but then were halted for a further hour, while American-made Phantoms of the Iranian Air Force took off. I thought they were training. They were in fact taking off on Khomeini’s orders to attack the rebel Kurds in the west. Later, in Karachi, I learned that two Phantoms had crashed, and the news was curiously sickening: such trim and deadly aircraft, so vulnerable the inadequately trained men within, half victims, yet men that morning obedient to the will of God and the Twelfth Imam and full of murder.

To Kurdistan, following the Phantoms, went Ayatollah Khalkhalli, Khomeini’s Islamic judge, as close to power as he had boasted only ten days before in Qom. In no time, moving swiftly from place to place in the August heat, he had sentenced forty-five people to death. He had studied for thirty-five years and was never at a loss for an Islamic judgement. When in one Kurdish town the family of a prisoner complained that three of the prisoner’s teeth had been removed and his eyes gouged out, Khalkhalli ordered a similar punishment for the torturer. Three of the man’s teeth were torn out on the spot. The aggrieved family then relented, pardoned the offender, and let him keep his eyes.

It was Islamic justice, swift, personal, satisfying; it met the simple needs of the faithful. But we hadn’t, in the old days, been told of this Iranian need. This particular promise of the revolution had been blurred or fudged; and we had read, mostly, Down with fascist Shah. Only Iranians, and some foreign scholars, knew that when Khomeini was a child — while the Qajar kings still ruled in Iran — Khomeini’s father had been killed by a government official; that the killer had been publicly hanged; that Khomeini had been taken by his mother to the hanging and told afterwards, “Now be at peace. The wolf has attained the fruit of its evil deeds.”

In his advertisement in The New York Times in January 1979, when he was still in exile in France, Khomeini had appealed to “the Christians of the world” as to people of an equal civilization. It was a different Khomeini who said in August, on Jerusalem Day (the day the Phantoms were sent against the Kurds): “The governments of the world should know that Islam cannot be defeated. Islam will be victorious in all the countries of the world, and Islam and the teachings of the Koran will prevail all over the world.”

That couldn’t have been said to the readers of The New York Times. Nor could this, spoken on the last Friday of Ramadan (and a good example of the medieval “logic and rhetoric” taught at Qom — certain key words repeated, used in varying combinations, and finally twisted): “When democrats talk about freedom they are inspired by the superpowers. They want to lead our youth to places of corruption… If that is what they want, then yes, we are reactionaries. You who want prostitution and freedom in every matter are intellectuals. You consider corrupt morality as freedom, prostitution as freedom… Those who want freedom want the freedom to have bars, brothels, casinos, opium. But we want our youth to carve out a new period in history. We do not want intellectuals.”

It was his call to the faithful, the people Behzad had described as lumpen. He required only faith. But he also knew the value of Iran’s oil to countries that lived by machines, and he could send the Phantoms and the tanks against the Kurds. Interpreter of God’s will, leader of the faithful, he expressed all the confusion of his people and made it appear like glory, like the familiar faith: the confusion of a people of high medieval culture awakening to oil and money, a sense of power and violation, and a knowledge of a great new encircling civilization. That civilization couldn’t be mastered. It was to be rejected; at the same time it was to be depended on.

The theme of Islam’s simultaneous hatred of and dependence on the West is one that recurs throughout the book. This is an essential contradiction within Islam: it cannot do without Western products and services, even as it totally despises Western culture.

1 comment:

Me thinks the West should leave Islam with the freedom to self-destruct.

Kind regs from Amsterdam,

Sag.

Post a Comment

All comments are subject to pre-approval by blog admins.

Gates of Vienna's rules about comments require that they be civil, temperate, on-topic, and show decorum. For more information, click here.

Users are asked to limit each comment to about 500 words. If you need to say more, leave a link to your own blog.

Also: long or off-topic comments may be posted on news feed threads.

To add a link in a comment, use this format:

<a href="http://mywebsite.com">My Title</a>

Please do not paste long URLs!

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.