The evil man is a source of fascination; ordinary persons wonder what impels such extremes of conduct. A lust for wealth? A common motive, undoubtedly. A craving for power? Revenge against society? Let us grant these as well. But when wealth has been gained, power achieved and society brought down to a state of groveling submission, what then? Why does he continue?

The response must be: the love of evil for its own sake.

The motivation, while incomprehensible to the ordinary man, is nonetheless urgent and real. The malefactor becomes the creature of his own deeds. Once the transition has been overpassed a new set of standards comes into force. The perceptive malefactor recognizes his evil and knows full well the meaning of his acts. In order to quiet his qualms he retreats into a state of solipsism, and commits flagrant evil from sheer hysteria, and for his victims it appears as if the world has gone mad.

— from The Face, by Jack Vance, p. 51 (DAW edition)

A reader in Israel emailed me to point out a resonance between the Baron’s words and a recently posted essay on the blog Hirhurim Musings. In “The Two Faces of Evil,” Gil Student cites rabbinical authority on the subject of human evil, and then muses on the topic himself:

Evil has two faces. The first — turned to the outside world — is what it does to its victim. The second — turned within — is what it does to its perpetrator. Evil traps the evildoer in its mesh. Slowly but surely he or she loses freedom and becomes not evil’s master but its slave.- - - - - - - - - -

Pharaoh is in fact (and this is rare in Tanakh) a tragic figure like Lady Macbeth, or like Captain Ahab in Melville’s Moby Dick, trapped in an obsession which may have had rational beginnings, right or wrong, but which has taken hold of him, bringing not only him but those around him to their ruin. This is signaled, simply but deftly, early in next week’s sedra when Pharaoh’s own advisors say to him: “Let the people go so that they may worship the Lord their G-d. Do you not yet realize that Egypt is ruined?” (10: 7). But Pharaoh has left rationality behind. He can no longer hear them.

It is a compelling narrative, and helps us understand not only Pharaoh but Hitler, Stalin and other tyrants in modern times. It also contains a hint — and this really is fundamental to understanding what makes the Torah unique in religious literature — of why the Torah teaches its moral truths through narrative, rather than through philosophical or quasi-scientific discourse on the one hand, myth or parable on the other.

Compare the Torah’s treatment of freewill with that of the great philosophical or scientific theories. For these other systems, freedom is almost invariably an either/or: either we are always free or we never are. Some systems assert the first. Many — those who believe in social, economic or genetic determinism, or historical inevitability — claim the second. Both are too crude to portray the inner life as it really is.

The belief that freedom is an all or nothing phenomenon — that we have it either all the time or none of the time — blinds us to the fact that there are degrees of freedom. It can be won and lost, and its loss is gradual. Unless the will is constantly exercised, it atrophies and dies. We then become objects not subjects, swept along by tides of fashion, or the caprice of desire, or the passion that becomes an obsession. Only narrative can portray the subtlety of Pharaoh’s slow descent into a self-destructive madness. That, I believe, is what makes Torah truer to the human condition than its philosophical or scientific counterparts.

Pharaoh is everyman writ large. The ruler of the ancient world’s greatest empire, he ruled everyone except himself. It was not the Hebrews but he who was the real slave: to his obstinate insistence that he, not G-d, ruled history. Hence the profound insight of Ben Zoma (Avot 4: 1): “Who is mighty?” Not one who can conquer his enemies but “One who can conquer himself.”

The idea of being enslaved to evil is an ancient one, but it is still hard to keep it in mind when regarding a monster such as Saddam Hussein. It may well be that Saddam deeply enjoyed the torture and slaughter he visited on his unfortunate victims. But was he acting out of what we would call free will? Or was he simply applying a shrewd intelligence to make the most effective choices among evil possibilities, without ever having the choice of forsaking evil itself?

Turning to a Christian perspective on the same issue, there is no one who wrote more lucidly on the topic of human evil than the great theologian C.S. Lewis.

But first: we have been taken to task recently by commenters for presuming to write essays on theological matters instead of simply citing Scripture. Here’s what Lewis had to say on this issue:

It is Christ Himself, not the Bible, who is the true word of God. The Bible, read in the right spirit and with the guidance of good teachers, will bring us to Him. We must not use the Bible as a sort of encyclopedia out of which texts can be taken for use as weapons.

One of the main tenets of Christian doctrine is that Christ is the sole mediator between oneself and God. The Bible is not the mediator; it is a guide to help us find our way to Him. Unthinking reliance on the Bible is form of idolatry, to my mind.

But back to C.S. Lewis. Here is an excerpt from The Screwtape Letters (Note: “the Enemy” in this book refers to God, since the letters in question are written from one devil to another):

In peace we can make many of them ignore good and evil entirely; in danger, the issue is forced upon them in a guise to which even we cannot blind them. There is here a cruel dilemma before us. If we promoted justice and charity among men, we should be playing directly into the Enemy’s hands; but if we guide them to the opposite behaviour, this sooner or later produces (for He permits it to produce) a war or a revolution, and the undisguisable issue of cowardice or courage awakes thousands of men from moral stupor. This, indeed, is probably one of the Enemy’s motives for creating a dangerous world — a world in which moral issues really come to the point. He sees as well as you do that courage is not simply one of the virtues, but the form of every virtue at the testing point, which means, at the point of highest reality. A chastity or honesty, or mercy, which yields to danger will be chaste or honest or merciful only on conditions. Pilate was merciful till it became risky.

When virtue reaches a testing point, it makes a choice. If the evil path is chosen, both virtue and the range of additional options are reduced. Evil becomes progressively easier to choose, until the path of life has no more forks, and only the route of evil is left.

Or, as Lewis put it in Mere Christianity:

People often think of Christian morality as a kind of bargain in which God says, ‘If you keep a lot of rules I’ll reward you, and if you don’t I’ll do the other thing.’ I do not think that is the best way of looking at it. I would much rather say that every time you make a choice you are turning the central part of you, the part of you that chooses, into something a little different from what it was before. And taking your life as a whole, with all your innumerable choices, all your life long you are slowly turning this central thing either into a creature that is in harmony with God, and with other creatures, and with itself, or else into one that is in a state of war and hatred with God, and with its fellow creatures, and with itself. To be the one kind of creature is heaven: that is, it is joy and peace and knowledge and power. To be the other means madness, horror, idiocy, rage, impotence, and eternal loneliness. Each of us at each moment is progressing to the one state or the other.

And human beings — contrary to modern secular-humanistic doctrine — are not born with the innate ability to make moral choices. This faculty must be learned, practiced, and consciously maintained.

Telling us to obey instinct is like telling us to obey ‘people.’ People say different things: so do instincts. Our instincts are at war…. Each instinct, if you listen to it, will claim to be gratified at the expense of the rest…

The forms that evil takes in the modern world can be quite subtle. Not every incarnation of it is as recognizable as Saddam or Stalin. From the preface to The Screwtape Letters:

I live in the Managerial Age, in a world of “Admin.” The greatest evil is not now done in those sordid “dens of crime” that Dickens loved to paint. It is not done even in concentration camps and labour camps. In those we see its final result. But it is conceived and ordered (moved, seconded, carried, and minuted) in clean, carpeted, warmed, and well-lighted offices, by quiet men with white collars and cut fingernails and smooth-shaven cheeks who do not need to raise their voice. Hence, naturally enough, my symbol for Hell is something like the bureaucracy of a police state or the offices of a thoroughly nasty business concern.

And now we reach the quintessence of modern bureaucratic evil, Socialism. From “God in the Dock”:

Of all tyrannies a tyranny exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It may be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end, for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.

The greatest achievement of evil in our time is to have convinced us of its non-existence. To the modern mind, citing evil as a motive behind anyone’s behavior is to make a categorical error. People are victims of circumstances, in need of counseling, suffering from an addictive disease, or denied moral agency by forces beyond their control. No one is evil.

The greatest achievement of evil in our time is to have convinced us of its non-existence. To the modern mind, citing evil as a motive behind anyone’s behavior is to make a categorical error. People are victims of circumstances, in need of counseling, suffering from an addictive disease, or denied moral agency by forces beyond their control. No one is evil.With the possible exception of George W. Bush, of course.

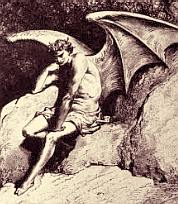

But to deny Lucifer is to make him stronger. Is it any wonder that the greatest and most virulent form of evil in recorded history has reared up before us now, at the dawn of the 21st century?

We stand before our secular altars, muttering incantations that deny it, but Evil will surely have the last word.

Hat tip: J B-D, via email.

The quotes from C.S. Lewis were obtained from a variety of online sources.

7 comments:

This might be the blog post of the decade. Thank you, Baron.

great.

one additional comment:

one can always turn away from evil and towards Hashem; it is always possible.

Pharaoh CHOOSES not to heed the ample warnings.

without choice there is no individual responsibility.

and the evil-doers are always responsible for their evil deeds.

for turning away.

Well done.

Evil becomes a habit however good its motives - i.e. revenge.

On a tangent, one of the objections I've heard from people regarding the ability for evil men to repent is that it would allow them to get off the hook, as it were. They ask, if hitler had repented on his deathbed, would he have gone to heaven? They miss the point, and your essay brings it right home: Hitler wouldn't be able to repent. The longer one does evil, the more keen one is to see it as good and the harder it is to convince one otherwise. It isn't impossible, but it becomes easier pull a hedgehog backward through a catflap than convince people they've made a mistake, even on the smallest of issues. It will be very painful for the hedgehog and you may just give up half way through, but it isn't impossible. The simple truth of the matter is, Hitler fervently believed that his evil was right and just. He reached a point where, while it was technically possible for him to reconsider and repent of his evil, mentally he was unable to take that course, even if he was given no other way.

Very well put.

Questions of morality are one of the main reasons why I got religion--not because I couldn't be moral before that, but because I couldn't make sense of the very concept of morality back then. Materialists speaking of morality had always sounded oxymoronic to me. The Daily Kos kids still do with their emphasis on "justice" ("No peace in the world without justice, no stopping of the bloodshed without addressing legitimate grievances", yada yada. Take a gander at this comment for an example).

I tackled the question of divine sovereignty vs. free will on my post All is Foreseen And Permission is Given, from September 7, 2006. The short version: I think they're both true at the same time, even if we don't understand how that can be.

By the way, the quote from Ben Zoma is better translated as, "Who is the mighty? The one who conquers his passion" (or "inclination"--the meaning of the Hebrew word yetzer is, I think, as elusive as that of the Buddhist term dukkha).

It should be remembered it was not Pharaoh himself who hardened his own heart. It was God who hardened his heart. This is confirmed in many instances all around the Bible.

The Calvinist principle is that human being is nothing but an automaton on the hands of merciless, vengeful God. God is the source of all evil. God makes some people evil in order that they would commit sins - and God would get a reason to punish them from the sins God himself ordered them to commit.

Contrary to what Reliapundit insisted, it wasn't Pharaoh's choice to not to heed ample warnings: it was God who made Pharaoh to not to hear those warnings. According to Bible, God is source of all evil - just as he is source of all good.

The dogma of predestination confirms this. By default everyone is sentenced to Hell at the moment they are born, but God saves a tiny fraction and grants them access to heaven. Likewise, God actively reprobates those who are not selected. Salvation is not by creed, not by deeds, not by choice and not by faith: it is nothing but lottery. If God didn't assign you the lot which provides a prize, your part is eternal torment and suffering in Hell. It is risky business to be born.

Judicially evil-doers are NOT responsible of their evil deeds (God has made them to commit evil), but God is not bound on human concepts of responsibility and fairness - God is God, and God punishes the innocent and the guilty with the same vigour. You cannot dictate God to be fair, just or merciful: God does exactly what he wants.

..

The moral of this story is that everyone is born evil - not good. No matter whether Bible is true or not, human beings are evil to the boot and by default nothing but naked apes. We are animals and we possess all the instincts, lusts and desires each and every animal does. It is those animalistic tendencies which make us to be evil, selfish to the boot, desire power and wealth and sex and produce offspring.

To be fair, Nazism is far more biologically and scientifially honest ideology than Marxism. While both Marxism and Nazism trace their roots to Hegel, Nazism relies on biology, biologism, Darwinism and natural sciences while Marxism follows the sociological path. Sociology (like all Humanist studies) is more or less bullshit, but natural sciences are based on scientific method. Marxism promises heaven on earth but creates Hell: Nazism promises Hell and creates it.

To put it in nutshell: The bad thing on Marxism is that it does not work; the bad thing on Nazism is that it does. It is the basic concept of humanity: Nazism gets it correct while Marxism doesn't.

Yet we loathe Nazism to boot and certainly none of us would like to live in a Nazi state. Why this contradiction - an ideology which is scientifially honest and gets its picture of humanity correct is found extremely deprave and loathsome?

It is because of ethics and honesty. It is only by admitting your own evil and that you are actually nothing but worthless scum and deprave to boot you can recognize the evil in yourself and then do something with it. Any religion which promotes human being is somehow good or noble creature gets it wrong. Those religions who insist human beings are evil are right. Only by admitting this evil you are capable on repenting and doing something with the evil in yourself.

Why do Marxists and other secular humanists fail continuously? It is because they do not admit the truth of biology and natural sciences - that we are animals and as animals we are evil and selfish to the booth. They rather deny it and rather insist the inherent nobility and goodness of human being. And as long as they do so, they fail to see evil in themselves - and only build the hells on Earth as they do.

Post a Comment

All comments are subject to pre-approval by blog admins.

Gates of Vienna's rules about comments require that they be civil, temperate, on-topic, and show decorum. For more information, click here.

Users are asked to limit each comment to about 500 words. If you need to say more, leave a link to your own blog.

Also: long or off-topic comments may be posted on news feed threads.

To add a link in a comment, use this format:

<a href="http://mywebsite.com">My Title</a>

Please do not paste long URLs!

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.